COVID-19 and Health Disparities: Takeaways from our Latest Conversation

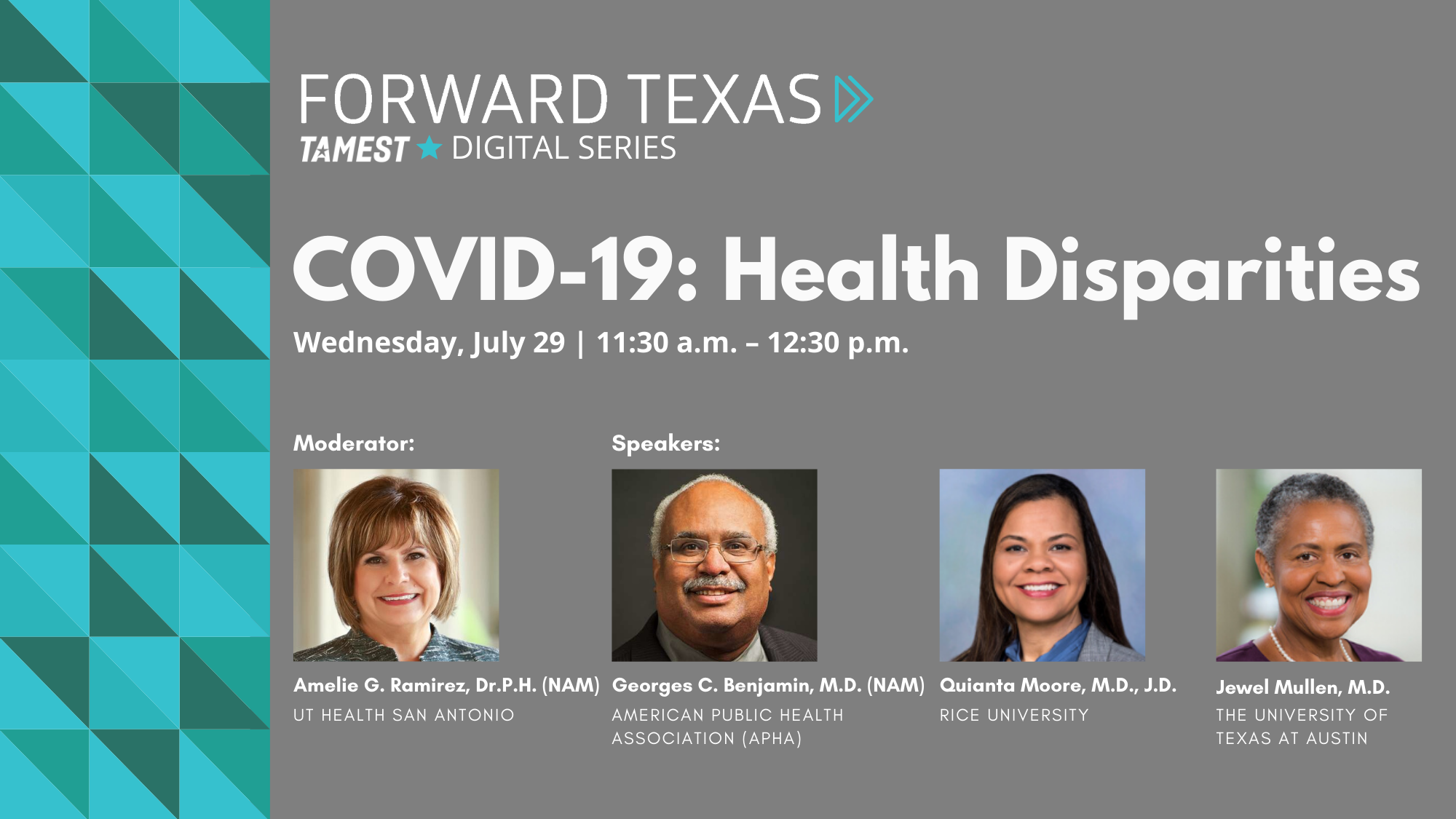

On Wednesday, July 29, TAMEST (The Academy of Medicine, Engineering and Science of Texas) held an important discussion on COVID-19: Health Disparities moderated by TAMEST Board President and leading health disparities researcher, Amelie G. Ramirez, Dr.P.H. (NAM), UT Health San Antonio.

Dr. Ramirez led a panel of population health experts to discuss how the COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted racial disparities in American health outcomes and explore opportunities to advance health equity during this crisis.

From long-standing social determinants for communities of color like poverty and lack of health insurance, the risks associated with job security for essential workers, to questions of vaccine testing equity, the panel discussed many facets of the complex issue of health disparities and COVID-19.

The panel included: Georges C. Benjamin, M.D. (NAM), Executive Director, American Public Health Association (APHA); Quianta Moore, M.D., J.D., Fellow in Child Health Policy Center for Health and Biosciences, Baker Institute for Public Policy, Rice University; and Jewel Mullen, M.D., Associate Dean for Health Equity, Associate Professor of Population Health and Internal Medicine, Dell Medical School, The University of Texas at Austin.

Find the key takeaways from our session discussion below:

1. Hospitalizations are a primary indication of health disparities associated with COVID-19.

Latinos, African Americans and Native Americans in the United States have been hospitalized due to COVID-19 at four to five times the rate of their white counterparts, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). For those under the age of 65, CDC data shows the COVID-19 death toll to be twice as high among people of color.

“This is an essential challenge and we know that we already have these disparities in a range of other diseases,” said Georges C. Benjamin, M.D. (NAM), Executive Director, American Public Health Association (APHA). “I don’t think any of us were surprised there were health disparities relating to COVID, but what was a surprise was the magnitude of the disparities from the disease.”

2. Exposure, susceptibility and social determinates among communities of color are three major causes of these disparities.

While African American, Native American and Latino communities all face unique challenges, research shows that they share commonalities correlating to disproportionate hospitalization rates due to COVID-19.

Such commonalities include: people of color are disproportionately impacted by structural racism and socioeconomic factors; they are more likely to be uninsured and experience higher rates of pre-existing and underlying health conditions such as heart disease or hyper-tension. These pre-existing health conditions amplify their risk of presenting severe symptoms related to COVID-19.

Additionally, people of color are more likely to be low-wage front-line workers than their non-Hispanic white counterparts and may be unable to self-isolate at home due to their housing situation.

“These are real lives and our communities are saying that they have to go on to work even if they have some symptoms because they are concerned about losing their jobs,” Dr. Ramirez said. “Here in San Antonio we had a situation where the father was working in a meatpacking company and living in a multi-generational home. He came back infected, the grandfather of the family was also impacted, and both of them passed away within days of each other. There is a lot to address with this issue.”

3. Health disparities in the U.S. are closely tied to systematic racism.

According to The American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP), hospitals and clinics that were once designated for racial and ethnic minorities continue to experience significant financial constraints and are often under-resourced and improperly staffed. These are just some of the ways inequities in access to and quality of health care can disproportionately affect people of color.

“If we think about any issue of equity, whether it be access to health care, access to health insurance … it really has to do with the fact that we have a history in this country that has systematically advantaged certain groups over other groups,” said Quianta Moore, M.D., J.D., Fellow in Child Health Policy Center for Health and Biosciences, Baker Institute for Public Policy, Rice University. “You really need to share power and resources with people from those communities.”

Dr. Moore said that the U.S. needs to stop creating policies that perpetuate structural racism and instead look at existing policies to evaluate the unanticipated consequences that are contributing to health disparities. This is the approach taken by Dr. Jewel Mullen while shaping health equity initiatives at both Ascension Seton and Dell Medical School at The University of Texas at Austin.

“We need to realize that health inequities might be rooted in the processes and not just the outcomes,” said Jewel Mullen, M.D., Associate Dean for Health Equity, Associate Professor of Population Health and Internal Medicine, Dell Medical School, The University of Texas at Austin.

Dr. Mullen explained that her role at Ascension Seton and Dell Medical School includes applying her expertise to think innovatively to help establish new ways of systematically addressing gaps in our health system.

4. An “infodemic” of bad information may have caused a delay in communities of color sheltering in place.

Dr. Benjamin defined the term “infodemic” as the rash of misinformation and disinformation being spread on social media and by word of mouth regarding COVID-19. These falsities had a specifically harmful effect on communities of color.

“Early on there were concerns about beliefs that African Americans were immune from this,” Dr. Benjamin said. “That resulted in a delay of a lot of Americans protecting themselves.”

He explained that, in addition to the rampant misinformation, disinformation from foreign influences and American influencers (including elected officials) is confusing communities. He said that the country must correct this by going into communities and sharing culturally competent information about the pandemic to correct concerns of vaccine safety, how COVID-19 spreads and who is at greatest risk.

5. Some testing centers show unconscious bias towards low-income communities.

When the pandemic began, the country saw an increase in drive-thru testing centers. However, what seems like an easy process for some created very real barriers for others.

“People who proudly set up drive-thru testing had to realize that some people can’t just drive through,” Dr. Mullen said.

On top of transportation being an early barrier for testing and care regarding COVID-19, a requirement to have a doctor’s note to get tested also created problems. Latinos have the highest uninsured rate of any racial or ethnic group in the country, with African Americans coming in second. This means that getting to a doctor can be more difficult and expensive for communities of color.

“If you don’t have a relationship with a primary care physician, can’t afford your co-pay to visit your doctor, or you don’t have a primary care doctor because you don’t have insurance, how are you going to get tested?” Dr. Benjamin asked.

6. When a COVID-19 vaccine is found, the U.S. needs to ensure equal access to it.

From ensuring diversity on research teams to all-encompassing sample sizes, the panel discussed the need to make sure communities of color are included in vaccine research happening now.

Dr. Mullen highlighted the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine’s ad hoc committee working to develop an overarching framework for allocation, which will assist policy makers in domestic and global health communities to plan for equitable allocation of vaccines against COVID-19.

When it comes to vaccine distribution, the panel agreed that it should be given to those who are at the highest risk, regardless of their color, with those on the front lines getting it first.

“I can telework, but the person who picks up my trash can’t,” Dr. Benjamin said. “The person picking up my trash, all things being equal, probably needs the vaccine more than I do and I can wait.”

7. The answer to health disparities in the U.S. should start at the policy level.

Dr. Moore said that The Families First Coronavirus Response Act (H.R. 6201) has had disproportionate impacts on low-income workers and communities of color. The bill was signed into law in March and requires certain employers to provide employees with paid sick leave or expanded family and medical leave for specified reasons related to COVID-19. However, under the law private employers with more than 500 employees or fewer than 50 employees may file for exemption as well as those in the health care industry, leaving most grocery and big box chains exempt.

“We need to stop creating policies that continue to perpetuate structural racism,” Dr. Moore said. “The Families First Coronavirus Response Act excluded the very employees that are at the front line and who are having to make the decision between going to work to put food on the table or staying at home with their children because there is a need or they are sick.”

Dr. Moore said change must start at the policy level.

“Number one is stop creating bad policy, that’s number one,” Dr. Moore said. “Number two is to look at existing policy and evaluate the unanticipated consequences of existing policy that has continued to perpetuate disparities. We need to fix those and close the gap.”

Full video of the session is available. Interested in future sessions? Visit our Forward Texas Digital Series page for more information.